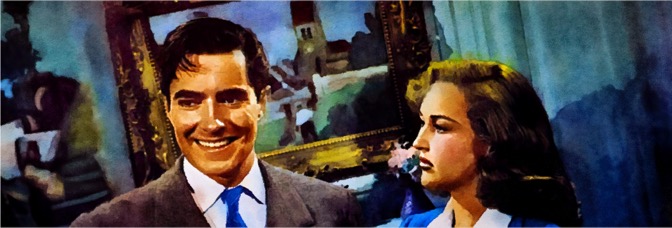

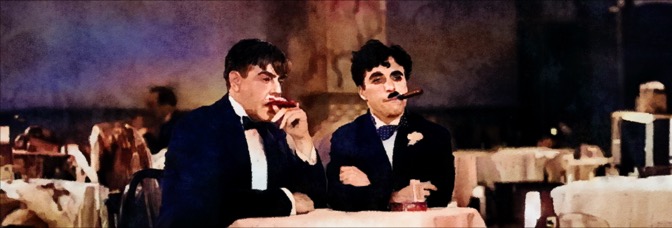

Betty Grable has a rough time in A Yank in the R.A.F. through no fault of her own. Her love triangle arc is the only thing going on for long stretches of the film. Despite being about brash narcissist Tyrone Power (the Yank) going over to England and joining the R.A.F.—while the U.S. was still operating under the Congressional Neutrality Acts (so pre-pre-Pearl Harbor)—Power doesn’t really have much of an arc. He’s eventually got the war story love triangle arc, as he and his commanding officer (the objectively less handsome and charming John Sutton) compete for Grable’s attentions. Power has a leg up (no pun) since he and Grable were together a year before when he ditched her for a long weekend to cat around with someone else.

Whenever Power has a scene where the story’s not following him, the introduction involves him trying to pick up on some lady. Nurses, mostly, but also British housewives. Given Grable’s working nights singing and dancing in a night club and doing Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) work during the day, she’s got dancing friends around, but they’re the only women Power doesn’t pick up on. The script feigns he’s a hopeless flirt—I mean, he’s Tyrone Power, after all, is he going to waste those gifts on one woman—but then he’s very intentional about catting around. It’s shitty.

Of course, all the dudes feel pretty entitled when it comes to Grable. Not dudes who know her, either. While she does meet Sutton at the airbase, he goes to call on her after drooling over her night-club performance. The recurring gag is fellow airman Reginald Gardiner is Grable’s biggest fan and, despite working with both Power and Sutton (even before Power and Sutton work together), he can’t get an introduction. In a better movie, Grable and Gardiner end up together, mostly because he’s got nothing insincere to woo her with. Power woos her with him being Tyrone Power and their physical chemistry—making things awkwarder is how well Power and Grable play together (at least at the beginning), but then he’s just a manipulative, sometimes way too physical prick–while Sutton’s a rich British gentleman. He can marry her and turn her into… well, if not a capital l lady, at least a lowercase l one. The film skirts around the respectability angle a few times, but it’s still there.

And still problematic.

In addition to having the most sympathetic characters, Grable and Gardiner easily gives the film’s best performances. Sutton and Power are both too shallow, albeit on opposite ends of the pond (pun). Sutton’s performance doesn’t have any passion or implication of it. As a result, when he courts Grable, she’s left mooning over someone who does nothing but try to negotiate a marriage contract with her. But he and Power also don’t bicker about R.A.F. business. The title’s A Yank in the R.A.F. and all, but Power’s experiences don’t matter until the third act when he gets to show those Germans what an American can do.

Another strange, timely aspect–Yank is all about showcasing the British war effort (with some phenomenal aerial photography), but it’s also about how they’re a bunch of wimps who will need the U.S. to save them one of these days. Sadly Power never reminds anyone he’s why they’re not speaking German from last time (also, the way the opening narration says “current war” is chilling).

But Power doesn’t have an arc, either. Yes, he gets more serious about his duties. But immediately. He’s supposedly the best flier the R.A.F. has got if they’d only give him a chance. It doesn’t go anywhere. He and Sutton go through a whole crash-landing arc, and it doesn’t go anywhere. At best, Power’s arc is meandering. More often, it’s either entirely stalled or entirely beside the point, so the film can focus on Grable having to choose between the dreamboat who mistreats her and the stiff upper lip who can buy her all the ponies she’ll ever want. Or something.

Grable does admirably well—she even keeps it together for the finale’s multiple big disses–and Yank’s often a great-looking film. Not sure why director King decides, somewhere in the second act, to try for moody lighting, though. Cinematographer Leon Shamroy ably pulls it off, but it just distracts. Though it’s distracting from Sutton and Power being dramatically inert, so… success?

But the version where Grable and Gardiner–Showgirl in the W.A.A.F.—is probably much better.

This post is part of the Betty Grable Blogathon hosted by Rebecca of Taking Up Room.

Ah, the days when the first part of an arc was really the first part of an arc. This issue opens with Selina—as Catwoman—chasing a kid through the streets of Gotham. He’s in Alleytown, a frankly gorgeous but rundown and dangerous neighborhood in Gotham. Artist Cameron Stewart busts ass on the scenery, so much so it’s like they should’ve just set the arc in Paris. But, no, it’s in Gotham. And we see more traditional Gotham towards the end of the issue when Slam’s out getting wasted and telling Holly how much he luvs Selina.

Ah, the days when the first part of an arc was really the first part of an arc. This issue opens with Selina—as Catwoman—chasing a kid through the streets of Gotham. He’s in Alleytown, a frankly gorgeous but rundown and dangerous neighborhood in Gotham. Artist Cameron Stewart busts ass on the scenery, so much so it’s like they should’ve just set the arc in Paris. But, no, it’s in Gotham. And we see more traditional Gotham towards the end of the issue when Slam’s out getting wasted and telling Holly how much he luvs Selina.

It’s a good but unfortunate issue of Black Panther. Writer Priest is firing on all cylinders, while the art is a Many Hands mishmash of styles—the issue credits Jimmy Palmiotti and Vince Evans (washes for Evans). But there’s also additional help from Alitha Martinez and Nelson DeCastro. So the art never looks consistent for more than a few pages. Some of Evans’s washes appear to be over pencils. Somehow they took the fun out of Joe Jusko pencils.

It’s a good but unfortunate issue of Black Panther. Writer Priest is firing on all cylinders, while the art is a Many Hands mishmash of styles—the issue credits Jimmy Palmiotti and Vince Evans (washes for Evans). But there’s also additional help from Alitha Martinez and Nelson DeCastro. So the art never looks consistent for more than a few pages. Some of Evans’s washes appear to be over pencils. Somehow they took the fun out of Joe Jusko pencils.

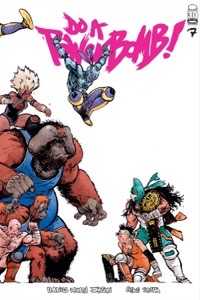

Creator Daniel Warren Johnson’s art on this last issue of Do a Powerbomb is fantastic, some of the best action art. In the series and beyond. Johnson really ups the ante with the final wrestling match, which has newly reunited (sort of) father and daughter wrestling team Cobrasun and Lona fighting God. God’s a big wrestling fan and a brutal opponent. Johnson does nothing with God as a character, which is fine. He’s in the middle of the biggest possible cop-out for a story—is Do a Powerbomb supposed to be a retelling of a Greek myth, maybe—so it’s nice he doesn’t stop for another big cop-out.

Creator Daniel Warren Johnson’s art on this last issue of Do a Powerbomb is fantastic, some of the best action art. In the series and beyond. Johnson really ups the ante with the final wrestling match, which has newly reunited (sort of) father and daughter wrestling team Cobrasun and Lona fighting God. God’s a big wrestling fan and a brutal opponent. Johnson does nothing with God as a character, which is fine. He’s in the middle of the biggest possible cop-out for a story—is Do a Powerbomb supposed to be a retelling of a Greek myth, maybe—so it’s nice he doesn’t stop for another big cop-out.

Side Effects feels like a series of public service announcements strung together. It doesn’t feel like mandatory public service announcements, which is something, but earnest only gets you so far. In the case of Side Effects, there’s nothing past so far. It’s a competent graphic novel about college freshman Hannah experiencing a mental health crisis while meeting a girl who also experiences mental health crises.

Side Effects feels like a series of public service announcements strung together. It doesn’t feel like mandatory public service announcements, which is something, but earnest only gets you so far. In the case of Side Effects, there’s nothing past so far. It’s a competent graphic novel about college freshman Hannah experiencing a mental health crisis while meeting a girl who also experiences mental health crises.

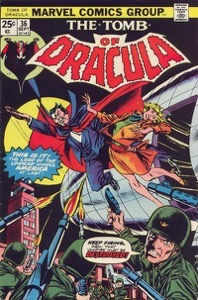

This issue’s a wonderful showcase for how seemingly nothing can go right for Tomb of Dracula, but thanks to the creators—even as writer Marv Wolfman crafts a silly tale, he’s still got the right artists with Gene Colan and Tom Palmer to give the issue a pulse. The cover promises Dracula’s coming to the United States. The issue delivers, with some caveats. First and foremost, the issue ends with Dracula at the airport. There are some hints at what’s next, but Wolfman’s padding.

This issue’s a wonderful showcase for how seemingly nothing can go right for Tomb of Dracula, but thanks to the creators—even as writer Marv Wolfman crafts a silly tale, he’s still got the right artists with Gene Colan and Tom Palmer to give the issue a pulse. The cover promises Dracula’s coming to the United States. The issue delivers, with some caveats. First and foremost, the issue ends with Dracula at the airport. There are some hints at what’s next, but Wolfman’s padding.

Wait, is Batman just supposed to be a bad dad? Did DC really not think giving him a kid through? Or does Monkey Prince writer Gene Luen Yang just get to flash his bonafides and characterize Batman as a complete dipshit?

Wait, is Batman just supposed to be a bad dad? Did DC really not think giving him a kid through? Or does Monkey Prince writer Gene Luen Yang just get to flash his bonafides and characterize Batman as a complete dipshit?

After Condors, I’m even more decided on the idea—Garth Ennis wanted to write a play. I’m not sure if he wanted to be a playwright or just write a play, but Condors is a play. The entire comic takes place in a bomb crater with four different soldiers fighting in the Spanish Civil War. Only one of them is Spanish. There’s an IRA man fighting on the side of the fascists. There’s a British socialist. Finally, there’s a German flier.

After Condors, I’m even more decided on the idea—Garth Ennis wanted to write a play. I’m not sure if he wanted to be a playwright or just write a play, but Condors is a play. The entire comic takes place in a bomb crater with four different soldiers fighting in the Spanish Civil War. Only one of them is Spanish. There’s an IRA man fighting on the side of the fascists. There’s a British socialist. Finally, there’s a German flier.

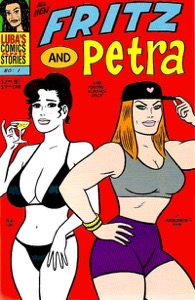

Creator Beto Hernandez released Luba's Comics and Stories simultaneous to the regular Luba series, which I knew when I was reading Luba, but didn’t attempt to read both in publication order. I’ve been a little worried about it, and, based on the first issue, it certainly seems possible there are going to be connections I’ll miss. However, I’m confident Beto will deliver, regardless of whether I forget some minutiae.

Creator Beto Hernandez released Luba's Comics and Stories simultaneous to the regular Luba series, which I knew when I was reading Luba, but didn’t attempt to read both in publication order. I’ve been a little worried about it, and, based on the first issue, it certainly seems possible there are going to be connections I’ll miss. However, I’m confident Beto will deliver, regardless of whether I forget some minutiae.