The Watermelon Woman is the story of video store clerk slash filmmaker Cheryl Dunye making a film about a 1930s Black female actor known only as “The Watermelon Woman.” At least initially. Dunye, in character, will spend the film discovering more and more about her subject, culminating in a documentary short. Surrounding Dunye dans le personnage’s professional aspirations are her friends and lovers. Dunye’s best friend is fellow video store clerk and videography business partner Valarie Walker.

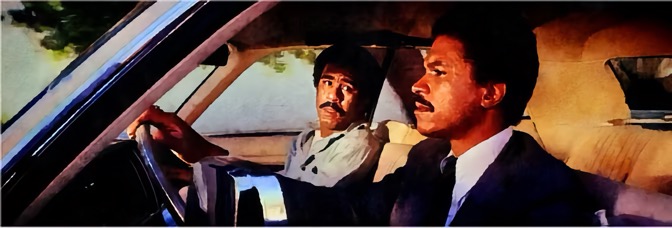

Walker’s the film’s comic relief (until she’s not). Woman is split between Dunye’s documentary footage in the film, shot on video; she and Walker’s professional videography outings, shot on video; the dramatic narrative, shot on 16mm; flashback film footage to 1930s movies, played on video; and occasional still photographs, sometimes on film, sometimes part of the video documentary, maybe sometimes just on video without being part of the documentary. Woman’s an editing masterclass. Dunye en tant que réalisateur and editor Annie Taylor do some sublime cutting, which isn’t always easy since Woman’s scenes all end in fade out. Dunye and Taylor will drop whole subplots in the fade-out, adding another layer. Woman’s about Dunye, the character, making the documentary, and the video stuff in Woman is footage from that documentary, but assembled—presumably—with agency by Dunye (the character). In the film made by Dunye, the writer and director. It plays incredibly naturally, down to Dunye just enjoying having the camera for the weekend and having fun.

And that natural feel also works in the reverse; when Dunye, the character, gets to the third act, she’s cagey about everything except her final product (which we don’t see her assemble). As well as Woman being the general story of her and Walker being two Black lesbian best buds in Philadelphia in the mid-1990s, with their dating and professional woes, it’s this particular, intentionally unexplored romantic drama about Dunye and Guinevere Turner. Turner’s a hip, upper-class WASP, who Walker can’t stand. Things just get worse when Dunye starts involving new video store clerk Shelley Olivier in their videography business; Walker really doesn’t like Olivier, and it’s when Walker stops being comic relief and instead Woman becomes this uncomfortable friendship drama, except Dunye (the filmmaker) doesn’t show much once Dunye (the character) strikes research gold.

Only then the research doesn’t reveal what Dunye (the character) expected, which plays out not in narrative drama but through videography narration.

Woman’s indie budget, but Dunye makes it work for the film instead of against it. The cost-saving measures (16mm only for controllable shots, video for the rest) and the occasional scene where they could’ve used another take (or ADR) add to Woman’s pulsing grip on reality. Because the film’s fiction. Dunye, the director, wanted to make a documentary about forgotten Black female actors of the 1930s and discovered they’d been forgotten. So she created the history for the film, with Zoe Leonard creating the period photographs while Dunye, Alexandra Juhasz, and Douglas McKeown made the old films. Woman’s from the better universe where women made independent movies in the 1930s and then made it to Hollywood. Just white women, so better comes with caveats.

Juhasz plays the 1930s director in photos and film clips, which strikes a chord with Dunye (the character). Except Juhasz is a white woman director involved with her Black female star (Lisa Marie Bronson), while Dunye is the Black woman director involved with a white girl (Turner). Dunye dans le personnage’s relationship with the material changes orbits during the film multiple times, often in reaction to events shown in the “uncut” footage from the documentary shoots.

It’s sublime narrative weaving.

With fades to and from black transitioning every scene, Dunye (often thanks to Walker) gets some great mic drop moments, and there are numerous good, encapsulated scenes. There are some definite standouts, but watching Camille Paglia say interracial dating didn’t exist in the thirties because Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? was in the sixties….

It’s hilarious. And one assumes Dunye just asked Paglia to play the bit like she’s a male film professor.

Technically, Woman’s outstanding. In addition to that wondrous cutting, Michelle Crenshaw’s photography is fantastic. The 16mm sequences are exquisite. Really good score from Paul Shapiro.

Watermelon Woman’s awesome.

Sometimes the snow comes down in June, and all that business because out of nowhere… Archangel is really good. It’s not the best of writer Garth Ennis’s War Story: Volume Two, which is only not a joke award because of that David Lloyd story, but Archangel definitely makes up for the previous couple entries. Now, I read Volume Two in the collection order, not the publication order, and I remain convinced they intentionally started with the superior Lloyd story. Archangel is the finale in both orders, so Ennis (and perhaps his Vertigo editors) saved the second-best for the last.

Sometimes the snow comes down in June, and all that business because out of nowhere… Archangel is really good. It’s not the best of writer Garth Ennis’s War Story: Volume Two, which is only not a joke award because of that David Lloyd story, but Archangel definitely makes up for the previous couple entries. Now, I read Volume Two in the collection order, not the publication order, and I remain convinced they intentionally started with the superior Lloyd story. Archangel is the finale in both orders, so Ennis (and perhaps his Vertigo editors) saved the second-best for the last.

Another issue in and I’m fine not having read Luba’s Comics and Stories in line with the Luba series. I was worried about it before, but this issue features a direct continuation of Fritz’s flashback reveals from last issue and has a character who dies in the Luba run appearing. So it’s like old home week a bit.

Another issue in and I’m fine not having read Luba’s Comics and Stories in line with the Luba series. I was worried about it before, but this issue features a direct continuation of Fritz’s flashback reveals from last issue and has a character who dies in the Luba run appearing. So it’s like old home week a bit.

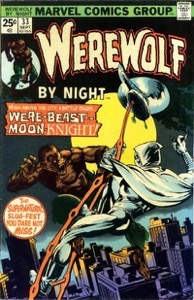

It’s a lackluster but not bad Werewolf by Night, which is one hell of a compliment, but what else are you going to do with this book. Writer Doug Moench finally resolves the mysterious Committee out to get Jack Russell since the first issue. Or at least by the third issue. They hired Moon Knight to deliver him, promising $10,000 in U.S. greenbacks, then make Moon Knight wait until human Jack wolfs out. Will mercenary Moon Knight let the Committee turn Wolfman Jack into a relentless killer, probably starting with the Committee’s latest captives—Jack’s best girl, Topaz, and his little sister, Lisa.

It’s a lackluster but not bad Werewolf by Night, which is one hell of a compliment, but what else are you going to do with this book. Writer Doug Moench finally resolves the mysterious Committee out to get Jack Russell since the first issue. Or at least by the third issue. They hired Moon Knight to deliver him, promising $10,000 in U.S. greenbacks, then make Moon Knight wait until human Jack wolfs out. Will mercenary Moon Knight let the Committee turn Wolfman Jack into a relentless killer, probably starting with the Committee’s latest captives—Jack’s best girl, Topaz, and his little sister, Lisa.

Despite The Terminator not offering much (if anything) in the way of entertainment, much less artistry, I’m still intrigued by the series. Like, where’s the bottom? This issue has a guest penciler, Robin Ator, who’s probably the series worst (so far). The script’s from Jack Herman, who’s written more issues than anyone else at this point (pretty sure). Jim Brozman’s back inking, which is an inglorious task. But the comic’s even more of a mess than usual.

Despite The Terminator not offering much (if anything) in the way of entertainment, much less artistry, I’m still intrigued by the series. Like, where’s the bottom? This issue has a guest penciler, Robin Ator, who’s probably the series worst (so far). The script’s from Jack Herman, who’s written more issues than anyone else at this point (pretty sure). Jim Brozman’s back inking, which is an inglorious task. But the comic’s even more of a mess than usual.