Infinity 8 has quite the conclusion. The issue opens with a flashback, an origin story—of sorts—for both the time-hopping captain and his faithful sidekick, Lieutenant Reffo. Reffo’s been the guy creeping on all of the female agents and, occasionally, recapping the mission. We find out in the flashback he’s been trained for just this position and isn’t actually a socially inept jackass; he’s got a computer-enhanced brain, so he’s just really smart and therefore doesn’t have time for social pleasantries.

Infinity 8 has quite the conclusion. The issue opens with a flashback, an origin story—of sorts—for both the time-hopping captain and his faithful sidekick, Lieutenant Reffo. Reffo’s been the guy creeping on all of the female agents and, occasionally, recapping the mission. We find out in the flashback he’s been trained for just this position and isn’t actually a socially inept jackass; he’s got a computer-enhanced brain, so he’s just really smart and therefore doesn’t have time for social pleasantries.

After the surprising flashback, which answers some questions about the eighty-eight Tonn Shar captains piloting the eighty-eight Infinity ships—questions writer Lewis Trondheim has never explicitly told the reader to ask, but in hindsight, certainly wasn’t discouraging the reader from thinking about. Unlike the introduction of the time-traveling robots (Hal is back this issue, teaming up with Reffo, delightfully), which came without significant foreshadowing, the Tonn Shar backstory has had some narrative shading. But nothing explicit enough for the opening reveal not to come as a surprise. Infinity 8’s resolution involves lots of red herring, but since time reset itself and so on, is it really red herring if it doesn’t spoil and stink?

I read Infinity 8 in the original French volume release cycle, not the split-into-three-issues format. However, given the number of callbacks in the finale, I’m reasonably sure you’re supposed to read Infinity 8 in a sitting or two–all of it. Trondheim brings back multiple characters from throughout the series as Reffo and Hal assemble an Infinity 8 all-star team to save the day. While Trondheim spends more time with some characters than others, he remembers to tie up loose ends for even the most tertiary. And I could not remember what he was tying up for some of them. Especially since the team-up allows the previous agents to chitchat, leading to further references.

Sometimes the former protagonists get action sequences to themselves, where they’re technically interchangeable, but they’ve got enough personality to drive themselves. Other times, Trondheim will give a return character some panels, or even a full page, just to vamp because he clearly likes writing the character. Thanks to Trondheim’s strong storytelling instincts and artist Killoffer’s imaginative renderings, either approach leads to sublime results, especially since Trondheim doesn’t shy away from mixing multiple sci-fi subgenres and Killoffer’s able to bring them all together stylistically.

Killoffer initially seems a little too rough. He uses computer-generated fractals for some space exteriors, particularly the space graveyard. It’s jarring—I’m still not sure about the galactic swirl being CGI—only to quickly become a captivating device. There’s so much intentionality in the objects when the action returns to the space graveyard it’s hard not to get lost in Killoffer’s rendered details.

The actual art seems a little rough at the start too. Killoffer’s got thick, almost reckless lines. They initially appear out of control, though—just like everything else with the art—the control soon becomes apparent. Until the End’s not my favorite art on Infinity, but it’s definitely in the top four. Once Reffo and Hal start their buddy picture, Killoffer’s comic timing hops the book up in line.

Killoffer’s also got the most packed story to contend with. While some of the previous volumes are almost entirely all action, End is all-action with different protagonists, in different (and new) settings, plus exposition. Reffo and Hal are simultaneously on the run, chasing someone else and learning how the series is going to end, though at different paces. While Reffo’s got the computer brain and so on, Hal knows more about what’s been going on in the book, so there’s a catch-up process. Finally, after seven volumes of Reffo being a pest, Trondheim turns him into a worthy protagonist. While still making him a pest.

It helps to have Hal around, even though Hal’s role in the volume isn’t quite what last time promised. He and Reffo have their buddy picture only until Reffo can manage on his own, then he (and Trondheim) almost immediately turn End into the team-up with the previous volumes’ agents. I get the need for narrative brevity, of course—End could be three times as long; there’s so much going on, and all of it’s entertaining—but there are only so many pages.

Trondheim employs a couple more narrative efficiencies in the epilogue, with the epilogue itself being something of an efficiency—only a couple characters really get a resolution to their character arcs. Trondheim’s script is mercilessly efficient.

Though he does allow the series, which has traversed time and space, to end on a one-liner. There’s some grandiosity to it, but it’s background. The joke’s the thing. And it works because, of course, it does. Though I wonder if you were marathoning Infinity 8 how it’d work. Maybe next time I read 8, it’ll be in a long sitting.

Until then, I’m obviously going to be missing this series. Trondheim and his various co-creators outdo themselves, time and again. Infinity 8 has been a damn good, damn fun read.

Writer Priest gets a guest artist—Vince Evans—to help him finish out the arc. At first it seems like Evans is going to be more action-oriented, but then he starts coming through with the comedy. He’s pretty bland with Ross (still) telling the story to his boss (slash girlfriend). It’s an even more Michael J. Fox Ross.

Writer Priest gets a guest artist—Vince Evans—to help him finish out the arc. At first it seems like Evans is going to be more action-oriented, but then he starts coming through with the comedy. He’s pretty bland with Ross (still) telling the story to his boss (slash girlfriend). It’s an even more Michael J. Fox Ross.

Writer Gerry Conway maintains his enthusiasm through this Legion entry, though he doesn’t have as many pages as usual to fill. Paul Kupperberg writes a backup—with pencils from Steve Ditko!–and eight fewer pages is what Conway needs.

Writer Gerry Conway maintains his enthusiasm through this Legion entry, though he doesn’t have as many pages as usual to fill. Paul Kupperberg writes a backup—with pencils from Steve Ditko!–and eight fewer pages is what Conway needs.

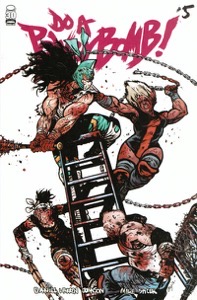

Creator Daniel Warren Johnson outdoes himself with this issue of Do a Powerbomb. It’s an almost entirely action issue, with Lona and Cobrasun fighting for the championship. The winner gets to resurrect a dead person of their choice—in Lona and Cobrasun’s case, her mom and his wife (actually, it’s unclear if they were married). Lona still doesn’t know Cobrasun’s her father; she assumes he’s helping resurrect her mom because he feels bad about killing her.

Creator Daniel Warren Johnson outdoes himself with this issue of Do a Powerbomb. It’s an almost entirely action issue, with Lona and Cobrasun fighting for the championship. The winner gets to resurrect a dead person of their choice—in Lona and Cobrasun’s case, her mom and his wife (actually, it’s unclear if they were married). Lona still doesn’t know Cobrasun’s her father; she assumes he’s helping resurrect her mom because he feels bad about killing her.

I’m resisting the urge to go back and figure out how many issues this day has been taking place–at least three, possibly four. Writer Marv Wolfman opens checking in on Frank Drake, who’s down in South America with some zombies after him. They’ve been after him for at least an issue, maybe two. Wolfman’s narration makes fun of Frank not being courageous, which is interesting since… we haven’t gotten anything out of him being a sap. Like, he’s not on some great character arc. He’s a jackass. It’s just never been clear Wolfman’s third-person narration thinks he’s a jackass too.

I’m resisting the urge to go back and figure out how many issues this day has been taking place–at least three, possibly four. Writer Marv Wolfman opens checking in on Frank Drake, who’s down in South America with some zombies after him. They’ve been after him for at least an issue, maybe two. Wolfman’s narration makes fun of Frank not being courageous, which is interesting since… we haven’t gotten anything out of him being a sap. Like, he’s not on some great character arc. He’s a jackass. It’s just never been clear Wolfman’s third-person narration thinks he’s a jackass too.

Writer Peter Milligan takes another approach with this issue’s narrative distance, back to Nina heavily narrating, but now she’s interrogating herself. As the deadline for Absolution draws near, she has to ask herself questions about who she wants to be. Or something. Milligan hints at what’s behind her character development, but he’s boxed Nina in, so she can’t do anything with it. She can’t even think it to herself. Otherwise, the reader would be clued in, and Milligan couldn’t do a twist.

Writer Peter Milligan takes another approach with this issue’s narrative distance, back to Nina heavily narrating, but now she’s interrogating herself. As the deadline for Absolution draws near, she has to ask herself questions about who she wants to be. Or something. Milligan hints at what’s behind her character development, but he’s boxed Nina in, so she can’t do anything with it. She can’t even think it to herself. Otherwise, the reader would be clued in, and Milligan couldn’t do a twist.

I meant to read War Stories in order of publication. Unfortunately, I got out of order here with J For Jenny, the second issue in the second volume but the first story in the collection. Because it’s David Lloyd on art again and, unlike the first volume, which ends with its Lloyd-illustrated story, War Stories: Part Two is coming out swinging.

I meant to read War Stories in order of publication. Unfortunately, I got out of order here with J For Jenny, the second issue in the second volume but the first story in the collection. Because it’s David Lloyd on art again and, unlike the first volume, which ends with its Lloyd-illustrated story, War Stories: Part Two is coming out swinging.

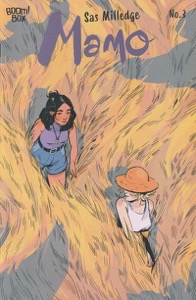

While it’s the worst issue of Mamo, it’s still a great comic. Creator Sas Milledge just doesn’t seem to have enough story for it and stretches. Orla and Jo deal with last issue’s cliffhanger, with Orla abandoning Jo and the crow. Except the crow seemed to have already left the girls. Jo can’t go after Orla because Orla took her bike (Jo’s), so Jo heads home. On the way, the crow asks why she isn’t going to Orla because the story’s obviously not at home; it’s with Orla.

While it’s the worst issue of Mamo, it’s still a great comic. Creator Sas Milledge just doesn’t seem to have enough story for it and stretches. Orla and Jo deal with last issue’s cliffhanger, with Orla abandoning Jo and the crow. Except the crow seemed to have already left the girls. Jo can’t go after Orla because Orla took her bike (Jo’s), so Jo heads home. On the way, the crow asks why she isn’t going to Orla because the story’s obviously not at home; it’s with Orla.

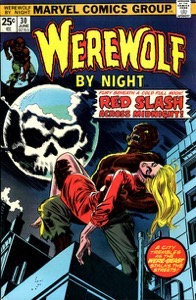

Did contemporary readers ever return their issues of Werewolf by Night, finally fed up with the false advertising on the cover? With its gorgeous Gil Kane cover, this issue promises a story entitled, Red Slash Across Midnight, and Wolfman Jack on the city’s rooftops, holding a blonde lady (so either his sister or Topaz, presumably). A blurb in the bottom right corner further promises, “A city trembles as the were-beast stalks the streets!”

Did contemporary readers ever return their issues of Werewolf by Night, finally fed up with the false advertising on the cover? With its gorgeous Gil Kane cover, this issue promises a story entitled, Red Slash Across Midnight, and Wolfman Jack on the city’s rooftops, holding a blonde lady (so either his sister or Topaz, presumably). A blurb in the bottom right corner further promises, “A city trembles as the were-beast stalks the streets!”

Even with the inexplicable cultural appropriation thread (yes, really) for the Terminator, this issue’s easily the best Terminator so far. Sure, they’re only on issue four—and on their third writer (Jack Herman takes over)—but it’s nearly okay. Until they decide to do “Terminator Meets Predator” only with Arnold as the bad guy… it’s got some real possibilities.

Even with the inexplicable cultural appropriation thread (yes, really) for the Terminator, this issue’s easily the best Terminator so far. Sure, they’re only on issue four—and on their third writer (Jack Herman takes over)—but it’s nearly okay. Until they decide to do “Terminator Meets Predator” only with Arnold as the bad guy… it’s got some real possibilities.

This issue opens with Selina narrating—remember, she hasn’t been narrating lately, so it took until the second or so page before I realized it was her (and she wasn’t talking about her sister, whose name I thought was Rebecca—it’s Maggie). There’s a girl named Rebecca (in flashback) who went bad; real Bonnie & Clyde stuff. Including what seems like moralizing but won’t be. Writer Ed Brubaker’s going to get back on the ball with narration as the issue progresses, and, luckily, the next scene is a winner.

This issue opens with Selina narrating—remember, she hasn’t been narrating lately, so it took until the second or so page before I realized it was her (and she wasn’t talking about her sister, whose name I thought was Rebecca—it’s Maggie). There’s a girl named Rebecca (in flashback) who went bad; real Bonnie & Clyde stuff. Including what seems like moralizing but won’t be. Writer Ed Brubaker’s going to get back on the ball with narration as the issue progresses, and, luckily, the next scene is a winner.

Writer Priest has a magical moment—or anti-magical—and artist Mark Texeira gets to do some great art, including shimmering pants, but the first thing to talk about with Black Panther #4 is the Everett Kenneth Ross photo reference.

Writer Priest has a magical moment—or anti-magical—and artist Mark Texeira gets to do some great art, including shimmering pants, but the first thing to talk about with Black Panther #4 is the Everett Kenneth Ross photo reference.

Half of this issue reads like writer Gerry Conway’s excited to be on the book. The other half reads like he’s miserable, detailing the petty bickering of superhero teen bros as they try to upstage one another. But when Conway’s writing about married colonists Bouncing Boy and Duo Damsel? He’s having a ball.

Half of this issue reads like writer Gerry Conway’s excited to be on the book. The other half reads like he’s miserable, detailing the petty bickering of superhero teen bros as they try to upstage one another. But when Conway’s writing about married colonists Bouncing Boy and Duo Damsel? He’s having a ball.

I’ve been getting the necromancer host of the Death Lyfe inter-dimensional wrestling tournament wrong; it’s Nectron, not Necro. So not an ape named Ape situation.

I’ve been getting the necromancer host of the Death Lyfe inter-dimensional wrestling tournament wrong; it’s Nectron, not Necro. So not an ape named Ape situation.

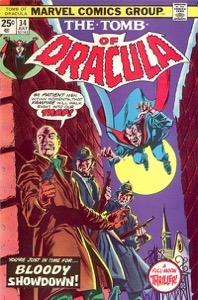

Artists Gene Colan and Tom Palmer have done some stunning issues of Tomb of Dracula, but this issue’s their best (so far). They’ve got the horror—the A plot is Quincy Harker watching a decomposing Dracula die on the carpet—they’ve got the time Dracula broke Harker’s back, so a flashback to an opera. There’s a political thriller sequence; there’s Dracula being regally evil, there’s Dracula as a bat in the winter, and there’s even a British pub scene. Plus, an epilogue (apparently) for Taj, and then checking on Rachel to make sure she’s alive.

Artists Gene Colan and Tom Palmer have done some stunning issues of Tomb of Dracula, but this issue’s their best (so far). They’ve got the horror—the A plot is Quincy Harker watching a decomposing Dracula die on the carpet—they’ve got the time Dracula broke Harker’s back, so a flashback to an opera. There’s a political thriller sequence; there’s Dracula being regally evil, there’s Dracula as a bat in the winter, and there’s even a British pub scene. Plus, an epilogue (apparently) for Taj, and then checking on Rachel to make sure she’s alive.

As I finished reading this issue of Absolution, I realized—despite artist Mike Deodato Jr.’s photo-referencing—the comic hasn’t established who they’re pitching with the lead role. When the creators muse about the adaptation, who’s playing Nina?

As I finished reading this issue of Absolution, I realized—despite artist Mike Deodato Jr.’s photo-referencing—the comic hasn’t established who they’re pitching with the lead role. When the creators muse about the adaptation, who’s playing Nina?

As a Garth Ennis war comic, I’m not sure Nightingale is the best War Story. As a War Story, it’s the best comic. Ennis’s script gets out of the way and lets David Lloyd’s art do its terrible magic. Because Nightingale is a nightmare, not just because it takes place on rough, cold waters in World War II, giving Lloyd all sorts of opportunities for literal stomach-churning art of the water. Ennis also digs in on it with the script, the words making the imagery all the more unsettling.

As a Garth Ennis war comic, I’m not sure Nightingale is the best War Story. As a War Story, it’s the best comic. Ennis’s script gets out of the way and lets David Lloyd’s art do its terrible magic. Because Nightingale is a nightmare, not just because it takes place on rough, cold waters in World War II, giving Lloyd all sorts of opportunities for literal stomach-churning art of the water. Ennis also digs in on it with the script, the words making the imagery all the more unsettling.

With each issue of Mamo, I consider starting by saying there’s no one like creator Sas Milledge in terms of visual pacing. At least for her character’s “performances.” Throughout the issue (and never concurrently), protagonists Orla and Jo have these reaction shots where Milledge has just paced it so perfectly their emotions come alive. Milledge’s other pacing devices are expert, but this particular one seems singular. It’s filmic in a way comics, even talking head comics, rarely attempt.

With each issue of Mamo, I consider starting by saying there’s no one like creator Sas Milledge in terms of visual pacing. At least for her character’s “performances.” Throughout the issue (and never concurrently), protagonists Orla and Jo have these reaction shots where Milledge has just paced it so perfectly their emotions come alive. Milledge’s other pacing devices are expert, but this particular one seems singular. It’s filmic in a way comics, even talking head comics, rarely attempt.