Between film festival premiere and eventual U.S. release, Penelope went from 104 minutes to just under ninety, apparently to get a family-friendly PG release, which makes sense since it’s based on a kids’ book. Except it’s not. Leslie Caveny’s screenplay is an original, meaning some of the film’s problems no longer have reasonable excuses.

Penelope is about twenty-five-year-old Christina Ricci. She’s a blue blood who lives in a fairy tale land. And she has the nose of a pig. Her ancestor threw over his pregnant maid girlfriend hundreds of years ago and married rich. The girlfriend killed herself and her mom, the town witch, cursed Ricci’s family. It just took hundreds of years for the curse to go active—the first female born will have “the face of a pig” until “one of her own kind” loves her.

Ricci’s parents are Catherine O’Hara and Richard E. Grant. Grant’s playing an American. Most of the Brits play Americans. Penelope’s urban fairytale land takes place in a British Manhattan. Maybe it’s in the universe where the U.S. lost the revolution and the American elite suck up to the British–much better movie.

Sadly, O’Hara’s not playing a Brit. It’d be hilarious. She’s the overbearing mom who wants Ricci to get married so she no longer has a pig’s face. Except Ricci doesn’t have a pig’s face, she has a pig’s nose–and pig-ish ears. We never see the ears. Will Ricci break the curse with true love from pauper James McAvoy or moneyed love with loathsome Simon Wood? Will it even matter?

Part of the gag is anytime a prospective bachelor meets Ricci, upon seeing her face, he runs away. The only one not to run is McAvoy, first because he doesn’t see her, then because he’s… transfixed. I assumed Penelope was based on a kids’ book because the only way the story makes sense is if, in the book, Ricci’s actually got a pig face. Then the story’s about some dude loving her for the real her, which has the added texture of Ricci and O’Hara’s most frequent repeat conversation being about how Ricci isn’t really herself until she loses the nose.

Except. It’s just a big, pushed-up nose. It’s a prosthetic. It’s not like it moves around. It’s not like it’s not well-kept. The movie also misses a really obvious opportunity about Ricci’s first kiss, though maybe in the original cut, there’s another one.

Ricci tries her best to act without being able to use half her face, thanks to the prosthetic. Her eyebrow work is phenomenal. Though there’s nothing she can do with the part, not with the writing, her costars, or the directing.

Besides Ricci, the best performances are Reese Witherspoon (who produced Penelope and, given selling her production company for a billion dollars, clearly got better at it after this movie) and Peter Dinklage. Witherspoon’s not bad, but she’s not successful either. I’m not even sure—in the ninety-minute cut—Penelope even passes Bechdel. It definitely doesn’t because even if Witherspoon has a name when she meets Ricci… Ricci doesn’t have a name because she’s incognito. Witherspoon’s in it for a couple scenes.

Dinklage is bad.

He’s just not as bad as everyone else. O’Hara’s in a similar position to Ricci, except with an unlikable character. She’s just the overbearing mom. Grant and McAvoy are atrocious. They’re both doing American accents, and they’re both terrible at them. Sometimes when he’s quiet, Grant seems like he’ll be good when he speaks (he isn’t, but seems like it). McAvoy’s consistently atrocious.

And then there’s Simon Woods as the British blue-blood who runs away from Ricci and then teams up with paparazzi Dinklage to out the freak in the newspapers.

Penelope has a minor newspaper subplot and doesn’t even know how to do newspaper printing montages. Director Palansky is full-stop incompetent. With the actors, with the composition, with the tone, with okaying the montages. Even a slightly better director would’ve helped immensely. Palansky’s only good moments are because his crew isn’t wholly inept.

Someone could’ve gotten some hash out of Penelope—no pun (though there are endless pork-related puns in the film, and none of them are funny, and we never even see how they affect Ricci because it’s so poorly done). But not Palansky. Not without a profound rewrite. You could even keep the cast (maybe not Woods).

Or just give Ricci something where she gets to use the brows.

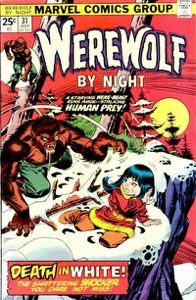

When I was a kid, this issue of Werewolf by Night was the most expensive because it featured the first appearance of “The Moon Knight,” a comic book weirdo. Werewolf proper hasn’t done any superhero crossovers, so Moon Knight could just be a seventies cosplayer. He’s not—he’s Marc Spector, mercenary, hired by The Committee to procure them one Jack Russell, werewolf. By night.

When I was a kid, this issue of Werewolf by Night was the most expensive because it featured the first appearance of “The Moon Knight,” a comic book weirdo. Werewolf proper hasn’t done any superhero crossovers, so Moon Knight could just be a seventies cosplayer. He’s not—he’s Marc Spector, mercenary, hired by The Committee to procure them one Jack Russell, werewolf. By night.

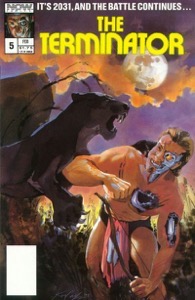

Truth be told, I have a hard time motivating myself with The Terminator. It’s not bad in peculiar ways related to the licensed property, and it doesn’t have some undiscovered talent doing fantastic work on it. But it’s had its moments. It’s also had irregular writers, with the original writer (and copyright holder on new characters in the indicia) Fred Schiller still not back and Jack Herman apparently the new series regular writer.

Truth be told, I have a hard time motivating myself with The Terminator. It’s not bad in peculiar ways related to the licensed property, and it doesn’t have some undiscovered talent doing fantastic work on it. But it’s had its moments. It’s also had irregular writers, with the original writer (and copyright holder on new characters in the indicia) Fred Schiller still not back and Jack Herman apparently the new series regular writer.

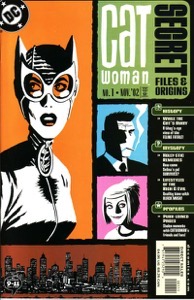

Presumably, regular writer Ed Brubaker needed someone to cover for him so he could work on Catwoman Secret Files, so Steven Grant fills in on the writing here–Brad Rader’s on pencils, with new-to-the-series Mark Lipka and Dan Davis on inks.

Presumably, regular writer Ed Brubaker needed someone to cover for him so he could work on Catwoman Secret Files, so Steven Grant fills in on the writing here–Brad Rader’s on pencils, with new-to-the-series Mark Lipka and Dan Davis on inks.

The issue begins with an Everett K. Ross scene; he’s debriefing the President about his latest adventure with Black Panther, only to quickly offend and have to roller-blade his way out of there. Writer Priest knows how to play Ross for comedy—I guess they couldn’t do the whitest white boy in the world in the MCU because Chris Pratt was already playing Starlord—but Priest continues to have problems with Ross professionally. He’s got a wacky reaction to the finale, but also, it was 1999, and maybe even the wokest CIA (sorry, OCP… OmniConsumer What?) agent is going to call armed response at a crowd of Black people.

The issue begins with an Everett K. Ross scene; he’s debriefing the President about his latest adventure with Black Panther, only to quickly offend and have to roller-blade his way out of there. Writer Priest knows how to play Ross for comedy—I guess they couldn’t do the whitest white boy in the world in the MCU because Chris Pratt was already playing Starlord—but Priest continues to have problems with Ross professionally. He’s got a wacky reaction to the finale, but also, it was 1999, and maybe even the wokest CIA (sorry, OCP… OmniConsumer What?) agent is going to call armed response at a crowd of Black people.

I’ve always had a soft spot for Steve Ditko’s art. Even thirty-ish years ago, when I was starting to recognize creators in Silver Age books—hunting down older comics to read—Ditko was already a reclusive, right-wing crank. No doubt complaining about wokeness since 1985. History’s just proven his being quiet about it was the only difference between him and many other comic creators.

I’ve always had a soft spot for Steve Ditko’s art. Even thirty-ish years ago, when I was starting to recognize creators in Silver Age books—hunting down older comics to read—Ditko was already a reclusive, right-wing crank. No doubt complaining about wokeness since 1985. History’s just proven his being quiet about it was the only difference between him and many other comic creators.

For the first time on Powerbomb, there’s cause for concern. I’m not actually concerned because I’ve got faith in creator Daniel Warren Johnson—he’s more than earned it by this point—but this issue’s at the “shit or get off the pot” moment in the series, and Johnson’s approach is to ask for five more minutes.

For the first time on Powerbomb, there’s cause for concern. I’m not actually concerned because I’ve got faith in creator Daniel Warren Johnson—he’s more than earned it by this point—but this issue’s at the “shit or get off the pot” moment in the series, and Johnson’s approach is to ask for five more minutes.

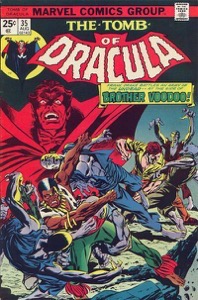

Besides the cover art having very little to do with the issue content—the cover shows Brother Voodoo fighting zombies; more on that adventure in a bit—this issue is an exemplar Tomb of Dracula. Writer Marv Wolfman has time to go overboard with the narration and exposition while still fitting a full horror comic story into the still very serialized Tomb narrative. It might also help there’s nothing with the other vampire hunters (and Frank Drake’s appearance comes with an asterisk).

Besides the cover art having very little to do with the issue content—the cover shows Brother Voodoo fighting zombies; more on that adventure in a bit—this issue is an exemplar Tomb of Dracula. Writer Marv Wolfman has time to go overboard with the narration and exposition while still fitting a full horror comic story into the still very serialized Tomb narrative. It might also help there’s nothing with the other vampire hunters (and Frank Drake’s appearance comes with an asterisk).

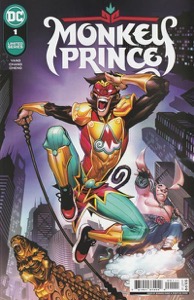

I’m not up on modern Batman takes, but… has everyone just agreed he’s a dick? Monkey Prince starts with a Batman cameo, then brings him (and Robin) into it for the cliffhanger. In addition to him being a dick, does every new book have a Batman cameo for the sales? Though Batman’s only on one of the variant covers. Maybe you assume Batman will be in all DC #1s?

I’m not up on modern Batman takes, but… has everyone just agreed he’s a dick? Monkey Prince starts with a Batman cameo, then brings him (and Robin) into it for the cliffhanger. In addition to him being a dick, does every new book have a Batman cameo for the sales? Though Batman’s only on one of the variant covers. Maybe you assume Batman will be in all DC #1s?

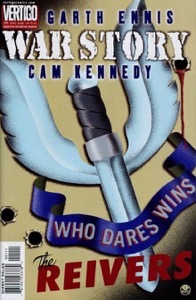

I think I figured out why The Reivers, the first issue of the second War Story volume, doesn’t start the collection. Because you might stop reading the collection. It’s kind of actually bad, but it’s also a slog. Writer Garth Ennis churns out dialogue to get through the comic. The artist is Cam Kennedy, who has the same expression for all of the talking heads. He’s slightly better at the action? But there’s minimal action. And it’s also very aggrandized.

I think I figured out why The Reivers, the first issue of the second War Story volume, doesn’t start the collection. Because you might stop reading the collection. It’s kind of actually bad, but it’s also a slog. Writer Garth Ennis churns out dialogue to get through the comic. The artist is Cam Kennedy, who has the same expression for all of the talking heads. He’s slightly better at the action? But there’s minimal action. And it’s also very aggrandized.

I’m hesitant to use the word “perfect” to describe a work. Mainly because perfect is very subjective. At a certain point in Mamo’s final chapter, I turned each page, holding my breath a little, waiting to see where creator Sas Milledge would take the book in its conclusion. But Milledge never hits those targets; she’s hitting different ones, better ones. I was hoping she’d find a way to give it a great ending, wheres Milledge was getting it to that great ending. So, in the sense it delivers—page by page—exactly what I wanted from it, Mamo doesn’t finish perfect.

I’m hesitant to use the word “perfect” to describe a work. Mainly because perfect is very subjective. At a certain point in Mamo’s final chapter, I turned each page, holding my breath a little, waiting to see where creator Sas Milledge would take the book in its conclusion. But Milledge never hits those targets; she’s hitting different ones, better ones. I was hoping she’d find a way to give it a great ending, wheres Milledge was getting it to that great ending. So, in the sense it delivers—page by page—exactly what I wanted from it, Mamo doesn’t finish perfect.

This issue does something beyond what I was expecting from Werewolf by Night. It surprised me. Writer Doug Moench—with artist Don Perlin co-plotting—actually surprised me. Now, they couch that surprise in some bad writing, but still. I didn’t know Werewolf had any surprises left in it.

This issue does something beyond what I was expecting from Werewolf by Night. It surprised me. Writer Doug Moench—with artist Don Perlin co-plotting—actually surprised me. Now, they couch that surprise in some bad writing, but still. I didn’t know Werewolf had any surprises left in it.

The Terminator, at least with writer Jack Herman steering the series… okay, it’s not good, but it’s not terrible. It’s not bad. While Herman never resolves the culturally appropriating white male Terminator who goes to the South American jungle and puts tribal markings on his fake(?) flesh to terrorize the locals, it’s at times thoughtful-ish sci-fi.

The Terminator, at least with writer Jack Herman steering the series… okay, it’s not good, but it’s not terrible. It’s not bad. While Herman never resolves the culturally appropriating white male Terminator who goes to the South American jungle and puts tribal markings on his fake(?) flesh to terrorize the locals, it’s at times thoughtful-ish sci-fi.

I sort of forgot about Secret Files. Especially this Catwoman one, even though I do remember Holly’s resurrection explanation being covered in it. Like I remember wanting to see how writer Ed Brubaker would address it. Now to decide if I want to spoil the reveal.

I sort of forgot about Secret Files. Especially this Catwoman one, even though I do remember Holly’s resurrection explanation being covered in it. Like I remember wanting to see how writer Ed Brubaker would address it. Now to decide if I want to spoil the reveal.