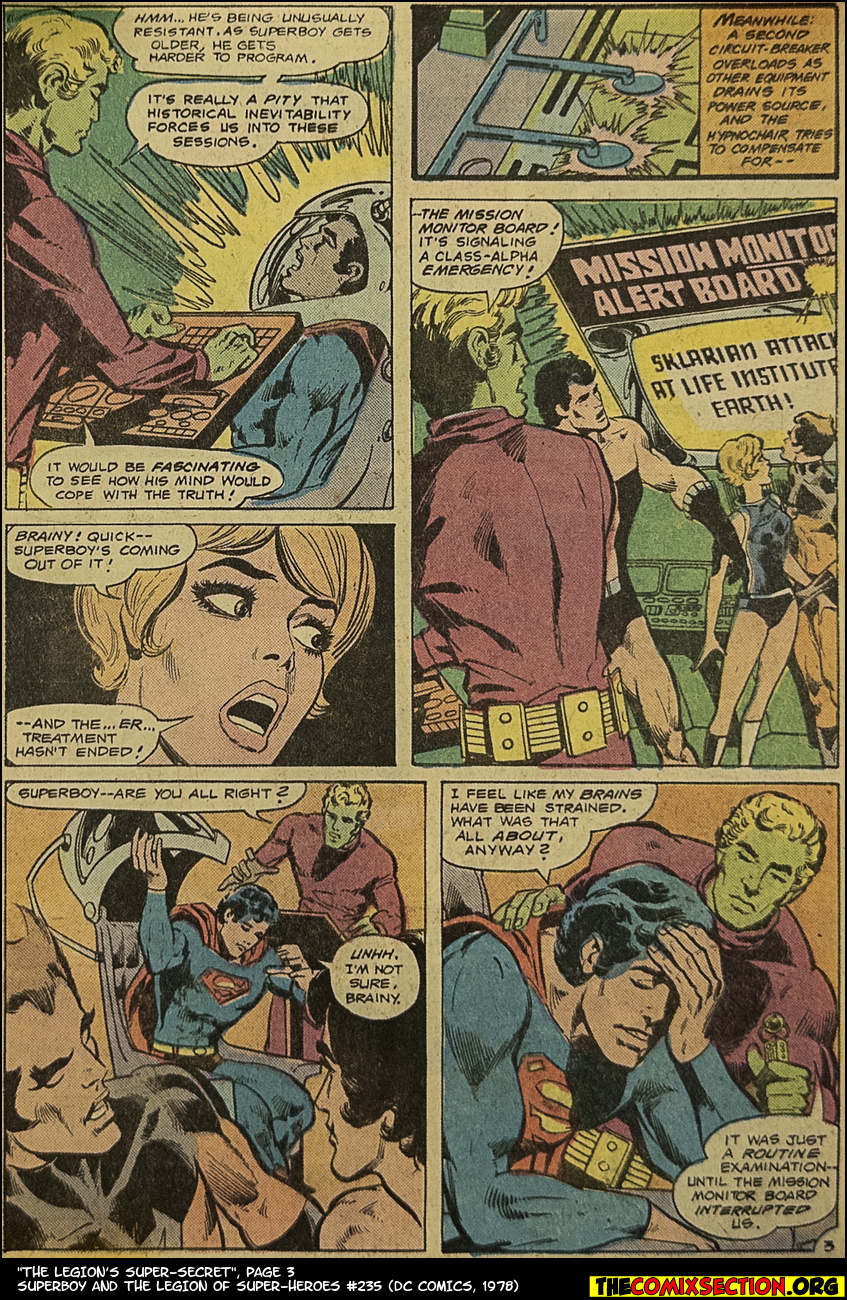

Will Eisner (editor, script, pencils, inks)

Joe Kubert (colors)

Sam Rosen (letters)

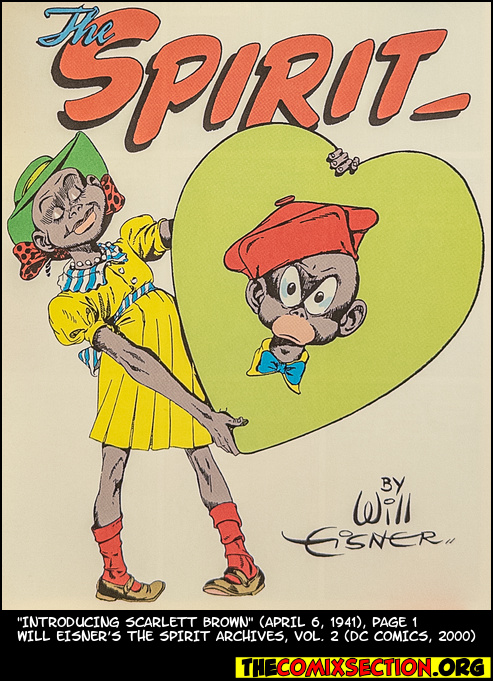

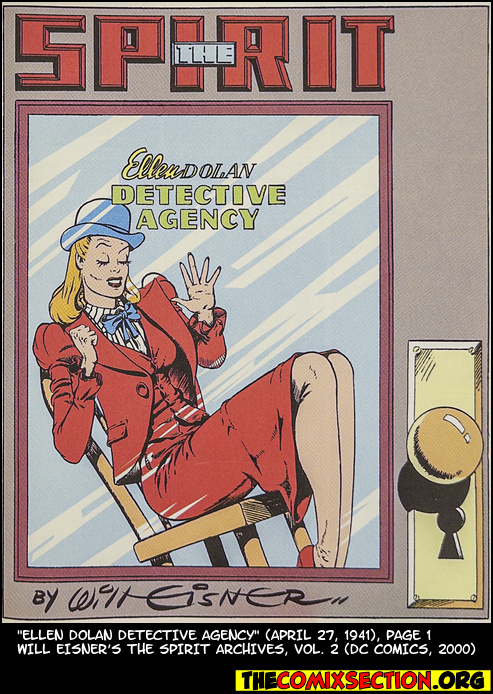

After her most recent experience in the workforce as a boxing manager, Ellen Dolan has moved on to running her own Detective Agency, presumably under the assumption if her father and the Spirit can do it, she’s got to be able to do it. And, other than a somewhat significant mistake, Ellen’s perfectly capable of playing private eye. She’s a great shot, too; since Spirit doesn’t carry a gun, when the need arises and Ellen’s got villains in her sights, her aim is true.

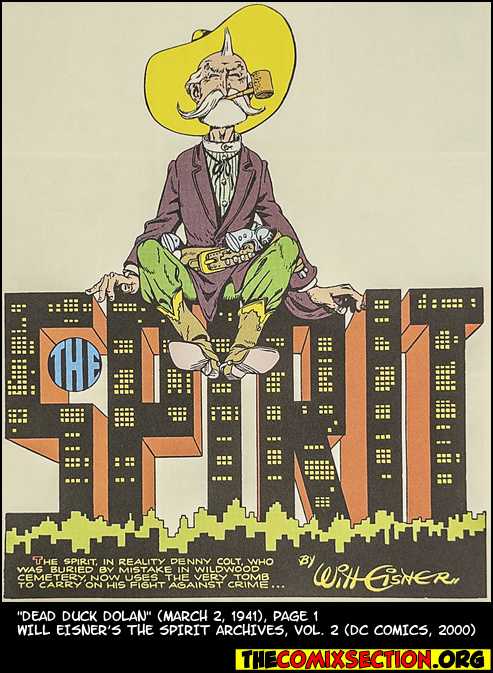

She is Dead Duck Dolan’s granddaughter, after all.

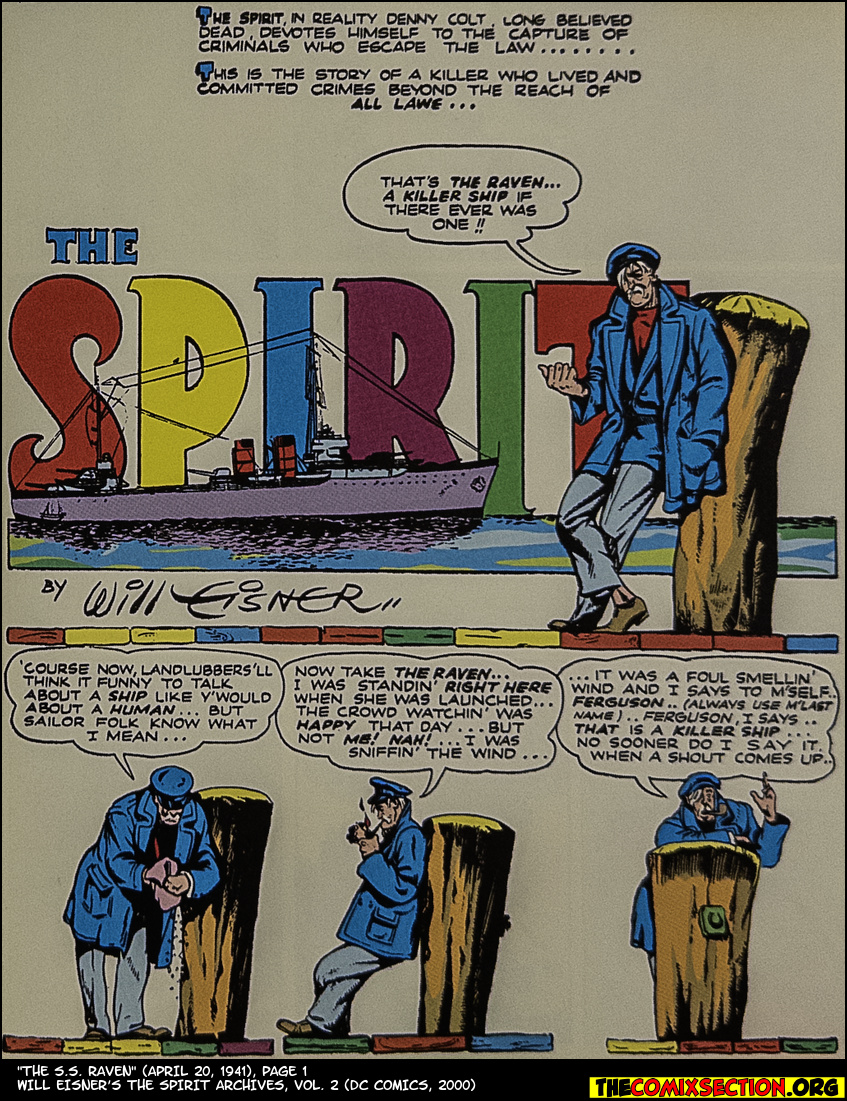

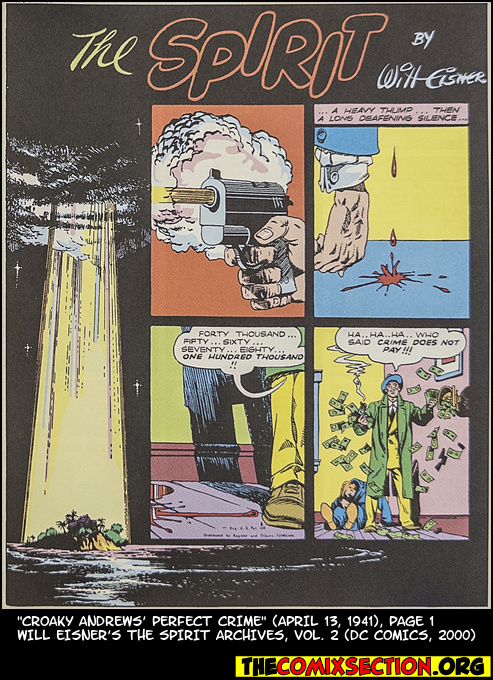

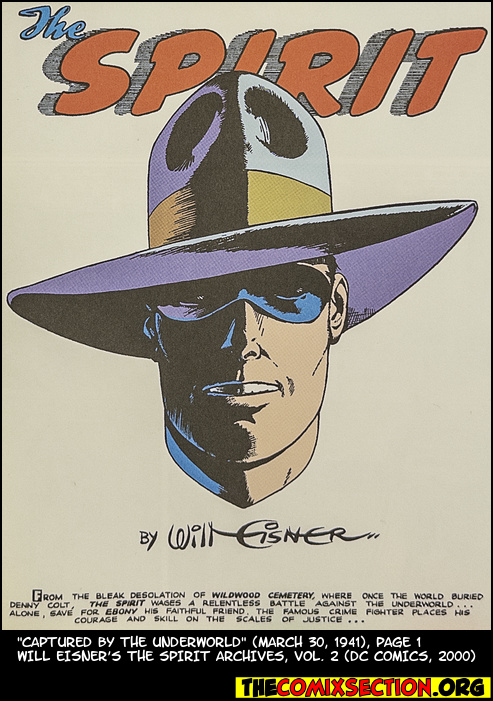

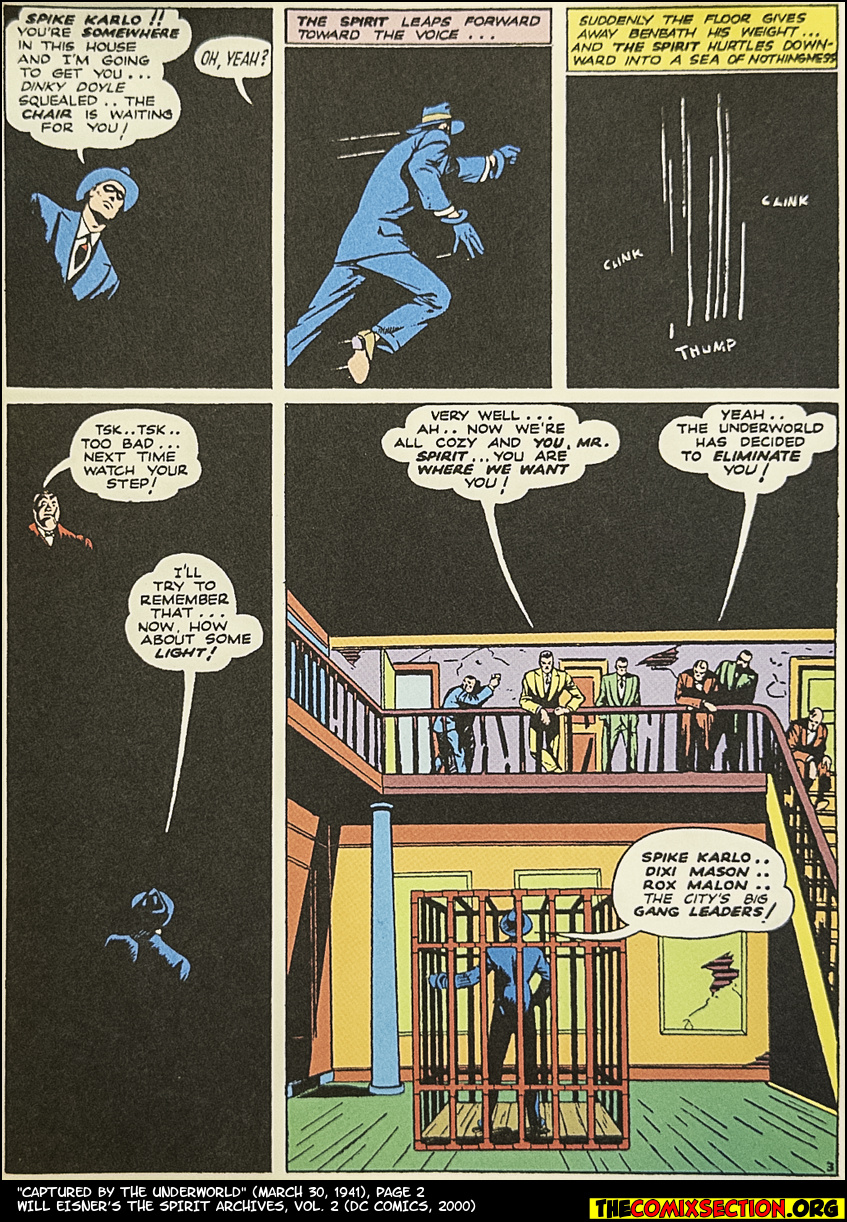

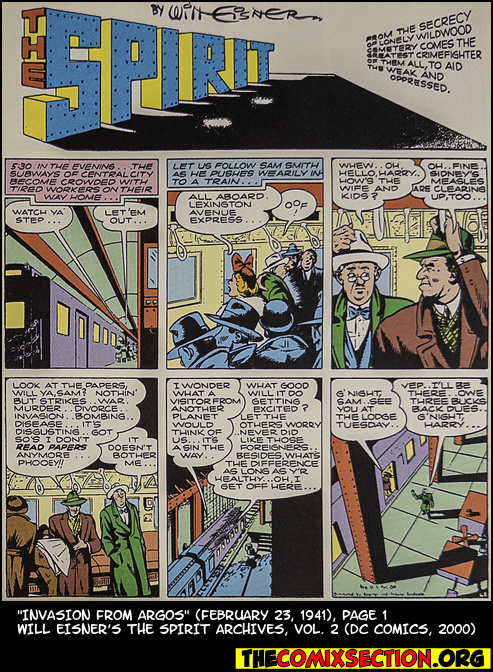

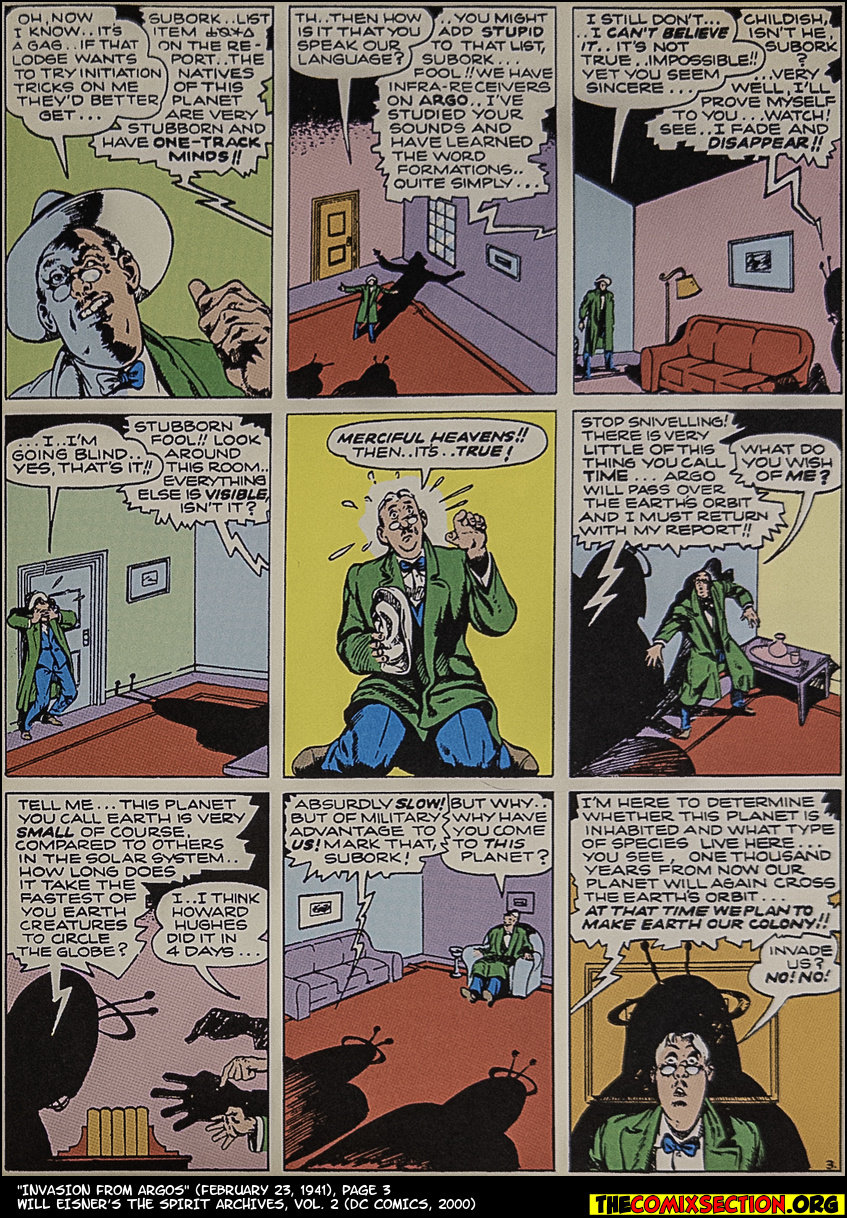

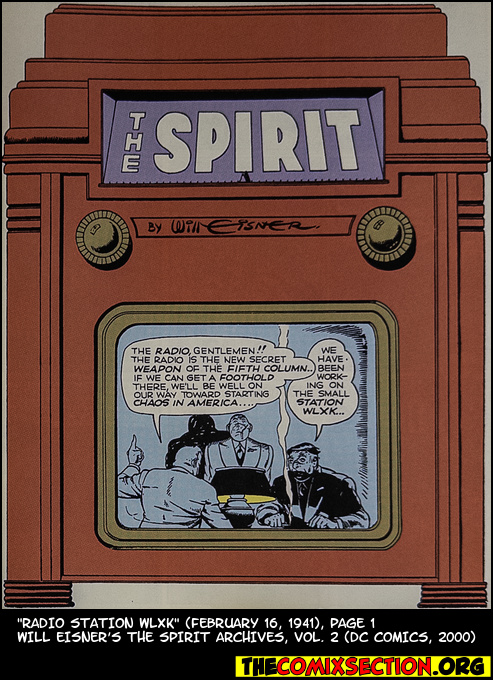

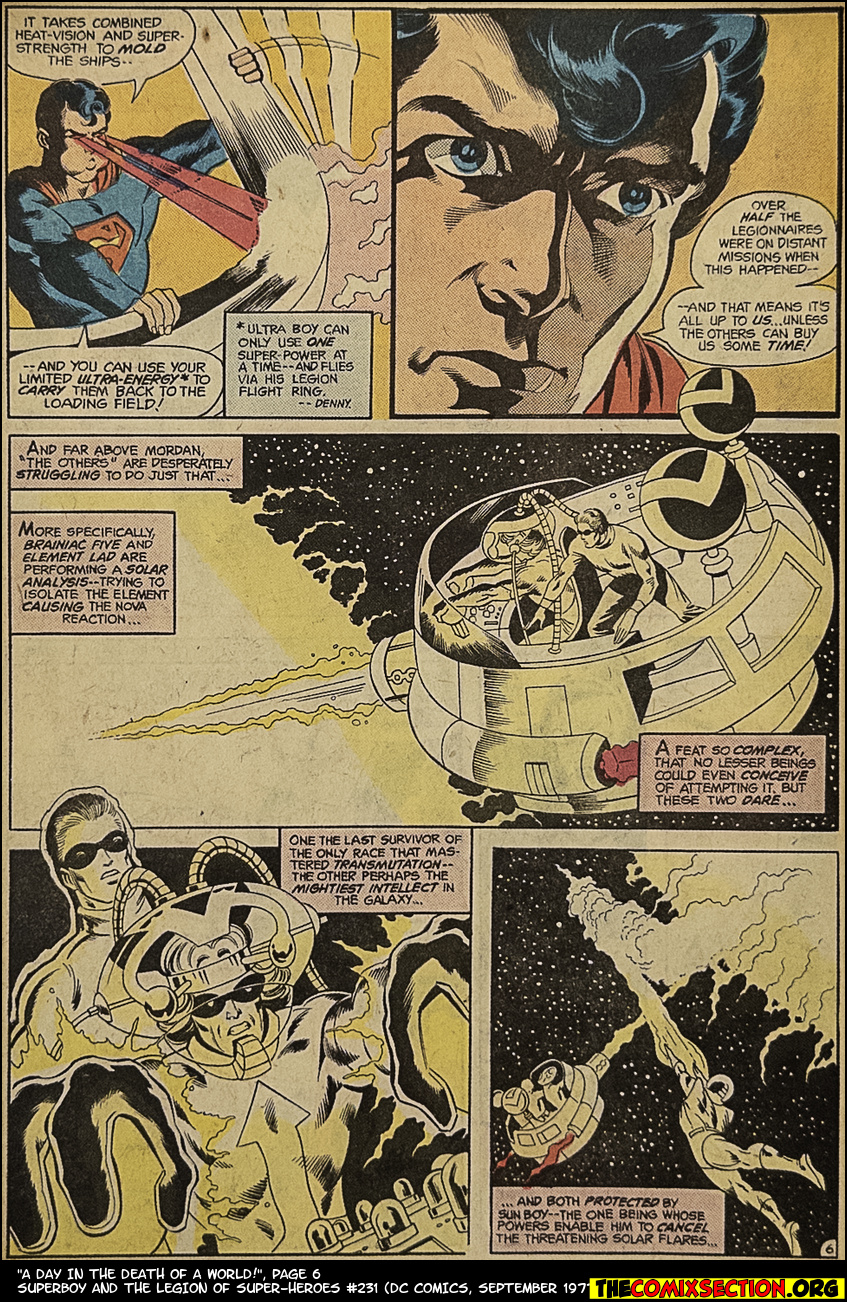

The splash page announces Ellen’s new vocation, but then the story heads to Wildwood to check in on Spirit and Ebony. Spirit’s reads about a failed military test and—seemingly accidentally—makes a profound observation about the nature of failed scientific experiments in fictional media. If something goes wrong, something must be wrong, because there’s no way the scientist would ever get to this stage without having thoroughly tested. Initially, Spirit’s enthusiasm for his reasoning seems like it’s going to be some jingoism (which is still there), but there’s more to it.

Especially since the military test in question involves Professor Ravel and his formula for a new explosive. Foreign agents would be very interested in getting their hands on that formula, which is why Ravel goes to find himself a gumshoe to protect him. He just happens to select Ellen Dolan Detective Agency.

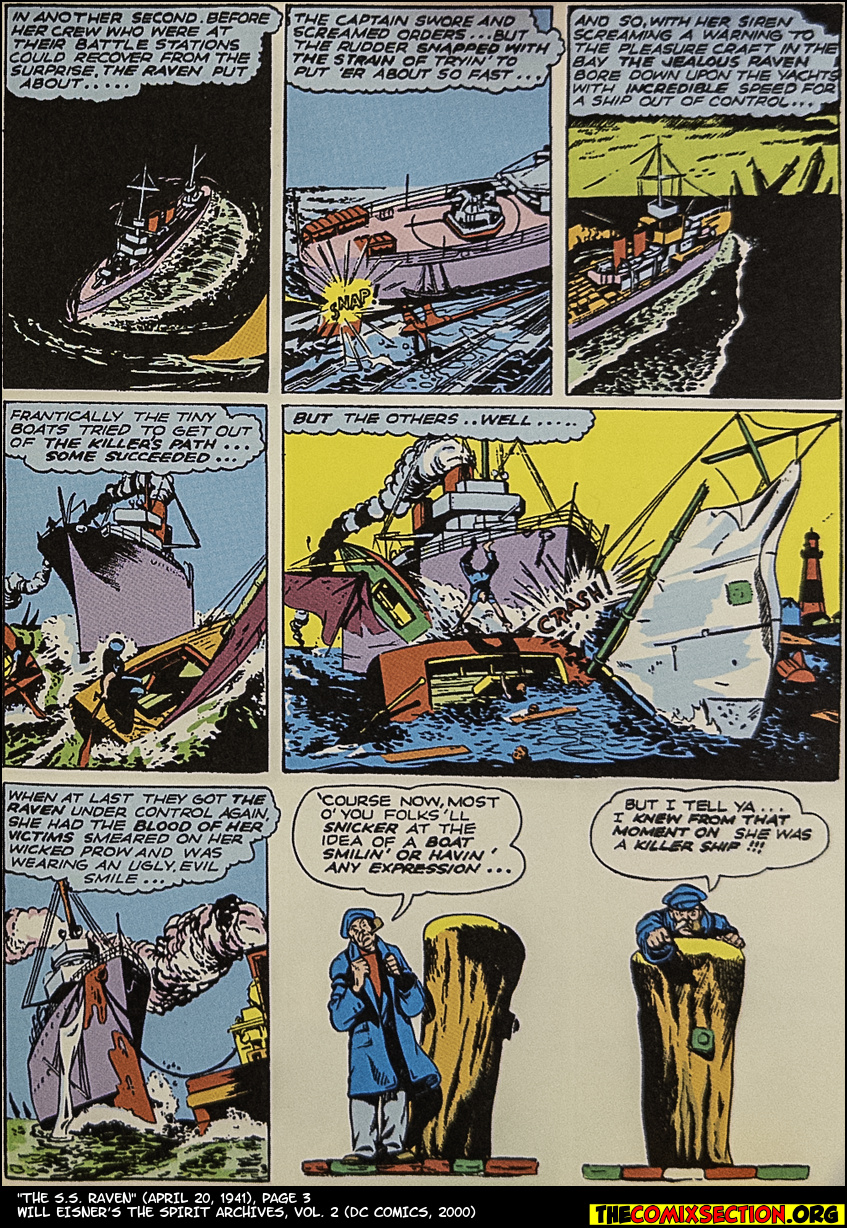

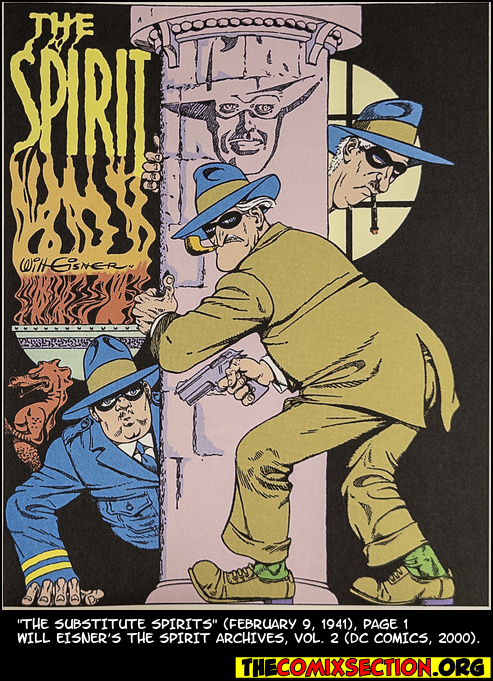

Spirit’s already on the case; he and Ellen quickly happen upon each other at the professor’s laboratory, Spirit puts his chemistry know-how to good use, Ellen puts her pistol-whipping to good use. It’s a build-up, as the showdown takes place at another location, one where foreign agents have the drop on the good guys.

Spirit gets to do some fisticuffs, Ellen gets to do some sharpshooting, and the strip manages to find its way to two punchlines. There’s the punchline to the mystery plot line, then—on the last page—a punchline to Ellen running her own detective agency. Eisner and studio find a cute ending, but they could’ve turned that last page into a whole strip of its own.

Lots of great art, with Ravel providing some comic relief while also keeping the plot perturbing. The fisticuffs sequences are particularly outstanding; after most of the strip hurries through the action, the fist fight slows it all down and finds Spirit’s visual rhythm. It’s perfectly paced.

And the bantering between Ellen and Spirit is nice. It’d play better if they were talking substantively, but there needs to be confusion and obstinacy to distract from the twists.

Ellen Dolan Detective is an excellent strip. It’s got a nice mix of plot twists, some fun character turns, visually engaging locations, and spectacular art. It’s also some of the strip’s best “wartime” strips to date. There’s the “War in Europe” subtext, which manages to be pronounced without taking up any additional space. Fantastic balance.

However—and lastly—the strip also the Spirit superhuman strength at one point. After going lights out from various pistol whips in the first half, Spirit takes big bruiser punches without flinching.

There’s not not a chance it’s supposed to be how Ellen sees him when he’s saving the day, which actually does work really well in the direct narrative and visual context… but is probably a reach.

Either way, great strip.